ploeh blog danish software design

The Specification contravariant functor

An introduction for object-oriented programmers to the Specification contravariant functor.

This article is an instalment in an article series about contravariant functors. It assumes that you've read the introduction. In the previous article, you saw an example of a contravariant functor based on the Command Handler pattern. This article gives another example.

Domain-Driven Design discusses the benefits of the Specification pattern. In its generic incarnation this pattern gives rise to a contravariant functor.

Interface #

DDD introduces the pattern with a non-generic InvoiceSpecification interface. The book also shows other examples, and it quickly becomes clear that with generics, you can generalise the pattern to this interface:

public interface ISpecification<T> { bool IsSatisfiedBy(T candidate); }

Given such an interface, you can implement standard reusable Boolean logic such as and, or, and not. (Exercise: consider how implementations of and and or correspond to well-known monoids. Do the implementations look like Composites? Is that a coincidence?)

The ISpecification<T> interface is really just a glorified predicate. These days the Specification pattern may seem somewhat exotic in languages with first-class functions. C#, for example, defines both a specialised Predicate delegate, as well as the more general Func<T, bool> delegate. Since you can pass those around as objects, that's often good enough, and you don't need an ISpecification interface.

Still, for the sake of argument, in this article I'll start with the Specification pattern and demonstrate how that gives rise to a contravariant functor.

Natural number specification #

Consider the AdjustInventoryService class from the previous article. I'll repeat the 'original' Execute method here:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Notice the Guard Clause:

if (productInventory.Quantity < 0)

Image that we'd like to introduce some flexibility here. It's admittedly a silly example, but just come along for the edification. Imagine that we'd like to use an injected ISpecification<ProductInventory> instead:

if (!specification.IsSatisfiedBy(productInventory))

That doesn't sound too difficult, but what if you only have an ISpecification implementation like the following?

public sealed class NaturalNumber : ISpecification<int> { public readonly static ISpecification<int> Specification = new NaturalNumber(); private NaturalNumber() { } public bool IsSatisfiedBy(int candidate) { return 0 <= candidate; } }

That's essentially what you need, but alas, it only implements ISpecification<int>, not ISpecification<ProductInventory>. Do you really have to write a new Adapter just to implement the right interface?

No, you don't.

Contravariant functor #

Fortunately, an interface like ISpecification<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor. This will enable you to compose an ISpecification<ProductInventory> object from the NaturalNumber specification.

In order to enable contravariant mapping, you must add a ContraMap method:

public static ISpecification<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>( this ISpecification<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { return new ContraSpecification<T, T1>(source, selector); } private class ContraSpecification<T, T1> : ISpecification<T1> { private readonly ISpecification<T> source; private readonly Func<T1, T> selector; public ContraSpecification(ISpecification<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { this.source = source; this.selector = selector; } public bool IsSatisfiedBy(T1 candidate) { return source.IsSatisfiedBy(selector(candidate)); } }

Notice that, as explained in the overview article, in order to map from an ISpecification<T> to an ISpecification<T1>, the selector has to go the other way: from T1 to T. How this is possible will become more apparent with an example, which will follow later in the article.

Identity law #

A ContraMap method with the right signature isn't enough to be a contravariant functor. It must also obey the contravariant functor laws. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the identity law for the ISpecification<T> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the identity law:

[Theory] [InlineData(-102)] [InlineData( -3)] [InlineData( -1)] [InlineData( 0)] [InlineData( 1)] [InlineData( 32)] [InlineData( 283)] public void IdentityLaw(int input) { T id<T>(T x) => x; ISpecification<int> projection = NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap<int, int>(id); Assert.Equal( NaturalNumber.Specification.IsSatisfiedBy(input), projection.IsSatisfiedBy(input)); }

In order to observe that the two Specifications have identical behaviours, the test has to invoke IsSatisfiedBy on both of them to verify that the return values are the same.

All test cases pass.

Composition law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that ContraMap obeys the composition law for contravariant functors:

[Theory] [InlineData( "0:05")] [InlineData( "1:20")] [InlineData( "0:12:10")] [InlineData( "1:00:12")] [InlineData("1.13:14:34")] public void CompositionLaw(string input) { Func<string, TimeSpan> f = TimeSpan.Parse; Func<TimeSpan, int> g = ts => (int)ts.TotalMinutes; Assert.Equal( NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))).IsSatisfiedBy(input), NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f).IsSatisfiedBy(input)); }

This test defines two local functions, f and g. Once more, you can't directly compare methods for equality, so instead you have to call IsSatisfiedBy on both compositions to verify that they return the same Boolean value.

They do.

Product inventory specification #

You can now produce the desired ISpecification<ProductInventory> from the NaturalNumber Specification without having to add a new class:

ISpecification<ProductInventory> specification = NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => inv.Quantity);

Granted, it is, once more, a silly example, but the purpose of this article isn't to convince you that this is better (it probably isn't). The purpose of the article is to show an example of a contravariant functor, and how it can be used.

Predicates #

For good measure, any predicate forms a contravariant functor. You don't need the ISpecification interface. Here are ContraMap overloads for Predicate<T> and Func<T, bool>:

public static Predicate<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Predicate<T> predicate, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => predicate(selector(x)); } public static Func<T1, bool> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Func<T, bool> predicate, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => predicate(selector(x)); }

Notice that the lambda expressions are identical in both implementations.

Conclusion #

Like Command Handlers and Event Handlers, generic predicates give rise to a contravariant functor. This includes both the Specification pattern, Predicate<T>, and Func<T, bool>.

Are you noticing a pattern?

The Command Handler contravariant functor

An introduction to the Command Handler contravariant functor for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about contravariant functors. It assumes that you've read the introduction.

Asynchronous software architectures, such as those described in Enterprise Integration Patterns, often make good use of a pattern where Commands are (preferably immutable) Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) that are often placed on a persistent queue and later handled by a background process.

Even if you don't use asynchronous processing, separating command data from command handling can be beneficial for your software's granular architecture. In perhaps his most remarkable contribution to our book, Steven van Deursen describes how this pattern can greatly simplify how you deal with cross-cutting concerns.

Interface #

In DIPPP the interface is called ICommandService, but in this article I'll instead call it ICommandHandler. It's a generic interface with a single method:

public interface ICommandHandler<TCommand> { void Execute(TCommand command); }

The book explains how this interface enables you to gracefully handle cross-cutting concerns without any reflection magic. You can also peruse its example code base on GitHub. In this article, however, I'm using a fork of that code because I wanted to make the properties of contravariant functors stand out more clearly.

In the sample code base, an ASP.NET Controller delegates work to an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> called inventoryAdjuster.

[Route("inventory/adjustinventory")] public ActionResult AdjustInventory(AdjustInventoryViewModel viewModel) { if (!this.ModelState.IsValid) { return this.View(nameof(Index), this.Populate(viewModel)); } AdjustInventory command = viewModel.Command; this.inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command); this.TempData["SuccessMessage"] = "Inventory successfully adjusted."; return this.RedirectToAction(nameof(HomeController.Index), "Home"); }

There's a single implementation of ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>, which is a class called AdjustInventoryService:

public class AdjustInventoryService : ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> { private readonly IInventoryRepository repository; public AdjustInventoryService(IInventoryRepository repository) { if (repository == null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(repository)); this.repository = repository; } public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); } }

The Execute method first loads the inventory data from the database, calculates how to adjust it, and saves it. This is all fine and good object-oriented design, and my intent with the present article isn't to point fingers at it. My intent is only to demonstrate how the ICommandHandler interface gives rise to a contravariant functor.

I'm using this particular code base because it provides a good setting for a realistic example.

Towards Domain-Driven Design #

Consider these two lines of code from AdjustInventoryService:

int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment);

Doesn't that look like a case of Feature Envy? Doesn't this calculation belong better on another class? Which one? The AdjustInventory Command? That's one option, but in this style of architecture Commands are supposed to be dumb DTOs, so that may not be the best fit. ProductInventory? That may be more promising.

Before making that change, however, let's consider the current state of the class.

One of the changes I made in my fork of the code was to turn the ProductInventory class into an immutable Value Object, as recommended in DDD:

public sealed class ProductInventory { public ProductInventory(Guid id) : this(id, 0) { } public ProductInventory(Guid id, int quantity) { Id = id; Quantity = quantity; } public Guid Id { get; } public int Quantity { get; } public ProductInventory WithQuantity(int newQuantity) { return new ProductInventory(Id, newQuantity); } public ProductInventory AdjustQuantity(int adjustment) { return WithQuantity(Quantity + adjustment); } public override bool Equals(object obj) { return obj is ProductInventory inventory && Id.Equals(inventory.Id) && Quantity == inventory.Quantity; } public override int GetHashCode() { return HashCode.Combine(Id, Quantity); } }

That looks like a lot of code, but keep in mind that typing isn't the bottleneck - and besides, most of that code was written by various Visual Studio Quick Actions.

Let's try to add a Handle method to ProductInventory:

public ProductInventory Handle(AdjustInventory command) { var adjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); return AdjustQuantity(adjustment); }

While AdjustInventoryService isn't too difficult to unit test, it still does require setting up and configuring some Test Doubles. The new method, on the other hand, is actually a pure function, which means that it's trivial to unit test:

[Theory] [InlineData(0, false, 0, 0)] [InlineData(0, true, 0, 0)] [InlineData(0, false, 1, 1)] [InlineData(0, false, 2, 2)] [InlineData(1, false, 1, 2)] [InlineData(2, false, 3, 5)] [InlineData(5, true, 2, 3)] [InlineData(5, true, 5, 0)] public void Handle( int initial, bool decrease, int adjustment, int expected) { var sut = new ProductInventory(Guid.NewGuid(), initial); var command = new AdjustInventory { ProductId = sut.Id, Decrease = decrease, Quantity = adjustment }; var actual = sut.Handle(command); Assert.Equal(sut.WithQuantity(expected), actual); }

Now that the new function is available on ProductInventory, you can use it in AdjustInventoryService:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

The Execute method now delegates its central logic to ProductInventory.Handle.

Encapsulation #

If you consider the Execute method in its current incarnation, you may wonder why it checks whether the Quantity is negative. Shouldn't that be the responsibility of ProductInventory? Why do we even allow ProductInventory to enter an invalid state?

This breaks encapsulation. Encapsulation is one of the most misunderstood concepts in programming, but as I explain in my PluralSight course, as a minimum requirement, an object should not allow itself to be put into an invalid state.

How to better encapsulate ProductInventory? Add a Guard Clause to the constructor:

public ProductInventory(Guid id, int quantity) { if (quantity < 0) throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( nameof(quantity), "Negative quantity not allowed."); Id = id; Quantity = quantity; }

Again, such behaviour is trivial to drive with a unit test:

[Theory] [InlineData( -1)] [InlineData( -2)] [InlineData(-19)] public void SetNegativeQuantity(int negative) { var id = Guid.NewGuid(); Action action = () => new ProductInventory(id, negative); Assert.Throws<ArgumentOutOfRangeException>(action); }

With those changes in place, AdjustInventoryService becomes even simpler:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Perhaps even so simple that the class begins to seem unwarranted.

Sandwich #

It's just a database Query, a single pure function call, and another database Command. In fact, it looks a lot like an impureim sandwich:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

In fact, it'd probably be more appropriate to move the null-handling closer to the other referentially transparent code:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId); productInventory = (productInventory ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Why do we need the AdjustInventoryService class, again?

Can't we move those three lines of code to the Controller? We could, but that might make testing the above AdjustInventory Controller action more difficult. After all, at the moment, the Controller has an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>, which is easy to replace with a Test Double.

If only we could somehow compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> from the above sandwich without having to define a class...

Contravariant functor #

Fortunately, an interface like ICommandHandler<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor. This will enable you to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> object from the above constituent parts.

In order to enable contravariant mapping, you must add a ContraMap method:

public static ICommandHandler<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>( this ICommandHandler<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { Action<T1> action = x => source.Execute(selector(x)); return new DelegatingCommandHandler<T1>(action); }

Notice that, as explained in the overview article, in order to map from an ICommandHandler<T> to an ICommandHandler<T1>, the selector has to go the other way: from T1 to T. How this is possible will become more apparent with an example, which will follow later in the article.

The ContraMap method uses a DelegatingCommandHandler that wraps any Action<T>:

public class DelegatingCommandHandler<T> : ICommandHandler<T> { private readonly Action<T> action; public DelegatingCommandHandler(Action<T> action) { this.action = action; } public void Execute(T command) { action(command); } }

If you're now wondering whether Action<T> itself gives rise to a contravariant functor, then yes it does.

Identity law #

A ContraMap method with the right signature isn't enough to be a contravariant functor. It must also obey the contravariant functor laws. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the identity law for the ICommandHandler<T> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the identity law:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("baz")] [InlineData("qux")] [InlineData("quux")] [InlineData("quuz")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("grault")] [InlineData("garply")] public void IdentityLaw(string input) { var observations = new List<string>(); ICommandHandler<string> sut = new DelegatingCommandHandler<string>(observations.Add); T id<T>(T x) => x; ICommandHandler<string> projection = sut.ContraMap<string, string>(id); // Run both handlers sut.Execute(input); projection.Execute(input); Assert.Equal(2, observations.Count); Assert.Single(observations.Distinct()); }

In order to observe that the two handlers have identical behaviours, the test has to Execute both of them to verify that both observations are the same.

All test cases pass.

Composition law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that ContraMap obeys the composition law for contravariant functors:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("baz")] [InlineData("qux")] [InlineData("quux")] [InlineData("quuz")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("grault")] [InlineData("garply")] public void CompositionLaw(string input) { var observations = new List<TimeSpan>(); ICommandHandler<TimeSpan> sut = new DelegatingCommandHandler<TimeSpan>(observations.Add); Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<int, TimeSpan> g = i => TimeSpan.FromDays(i); ICommandHandler<string> projection1 = sut.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))); ICommandHandler<string> projection2 = sut.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f); // Run both handlers projection1.Execute(input); projection2.Execute(input); Assert.Equal(2, observations.Count); Assert.Single(observations.Distinct()); }

This test defines two local functions, f and g. Once more, you can't directly compare methods for equality, so instead you have to Execute them to verify that they produce the same observable effect.

They do.

Composed inventory adjustment handler #

We can now return to the inventory adjustment example. You may recall that the Controller would Execute a command on an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>:

this.inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command);

As a first step, we can attempt to compose inventoryAdjuster on the fly:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId)); inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command);

Contra-mapping is hard to get one's head around, and to make matters worse, you have to read it from the bottom towards the top to understand what it does. It really is contrarian.

How do you arrive at something like this?

You start by looking at what you have. The Controller may already have an injected repository with various methods. repository.Save, for example, has this signature:

void Save(ProductInventory productInventory);

Since it has a void return type, you can treat repository.Save as an Action<ProductInventory>. Wrap it in a DelegatingCommandHandler and you have an ICommandHandler<ProductInventory>:

ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save);

That's not what you need, though. You need an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>. How do you get closer to that?

You already know from the AdjustInventoryService class that you can use a pure function as the core of the impureim sandwich. Try that and see what it gives you:

ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command));

That doesn't change the type of the handler, but implements the desired functionality.

You have an ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> that you need to somehow map to an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>. How do you do that?

By supplying a function that goes the other way: from AdjustInventory to ProductInventory. Does such a method exist? Yes, it does, on the repository:

ProductInventory GetByIdOrNull(Guid id);

Or, close enough. While AdjustInventory is not a Guid, it comes with a Guid:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId));

That's cool, but unfortunately, this composition cheats. It closes over command, which is a run-time variable only available inside the AdjustInventory Controller action.

If we're allowed to compose the Command Handler inside the AdjustInventory method, we might as well just have written:

var inv = repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId); inv = (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command); repository.Save(inv);

This is clearly much simpler, so why don't we do that?

In this particular example, that's probably a better idea overall, but I'm trying to explain what is possible with contravariant functors. The goal here is to decouple the caller (the Controller) from the handler. We want to be able to define the handler outside of the Controller action.

That's what the AdjustInventory class does, but can we leverage the contravariant functor to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> without adding a new class?

Composition without closures #

The use of a closure in the above composition is what disqualifies it. Is it possible to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> when the command object is unavailable to close over?

Yes, but it isn't pretty:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ValueTuple<AdjustInventory, ProductInventory> t) => (t.Item2 ?? new ProductInventory(t.Item1.ProductId)).Handle(t.Item1)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => (cmd, repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId)));

You can let the composing function return a tuple of the original input value and the projected value. That's what the lowest ContraMap does. This means that the upper ContraMap receives this tuple to map. Not pretty, but possible.

I never said that this was the best way to address some of the concerns I've hinted at in this article. The purpose of the article was mainly to give you a sense of what a contravariant functor can do.

Action as a contravariant functor #

Wrapping an Action<T> in a DelegatingCommandHandler isn't necessary in order to form the contravariant functor. I only used the ICommandHandler interface as an object-oriented-friendly introduction to the example. In fact, any Action<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor with this ContraMap function:

public static Action<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Action<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => source(selector(x)); }

As you can tell, the function being returned is similar to the lambda expression used to implement ContraMap for ICommandHandler<T>.

This turns out to make little difference in the context of the examples shown here, so I'm not going to tire you with more example code.

Conclusion #

Any generic polymorphic interface or abstract method with a void return type gives rise to a contravariant functor. This includes the ICommandHandler<T> (originally ICommandService<T>) interface, but also another interface discussed in DIPPP: IEventHandler<TEvent>.

The utility of this insight may not be immediately apparent. Contrary to its built-in support for functors, C# doesn't have any language features that light up if you implement a ContraMap function. Even in Haskell where the Contravariant functor is available in the base library, I can't recall having ever used it.

Still, even if not a practical insight, the ubiquitous presence of contravariant functors in everyday programming 'building blocks' tells us something profound about the fabric of programming abstraction and polymorphism.

Contravariant functors

A more exotic kind of universal abstraction.

This article series is part of a larger series of articles about functors, applicatives, and other mappable containers.

So far in the article series, you've seen examples of mappable containers that map in the same direction of projections, so to speak. Let's unpack that.

Covariance recap #

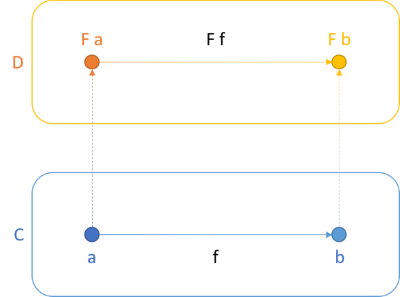

Functors, applicative functors, and bifunctors all follow the direction of projections. Consider the illustration from the article about functors:

The function f maps from a to b. You can think of a and b as two types, or two sets. For example, if a is the set of all strings, it might correspond to the type String. Likewise, if b is the set of all integers, then it corresponds to a type called Int. The function f would, in that case, have the type String -> Int; that is: it maps strings to integers. The most natural such function seems to be one that counts the number of characters in a string:

> f = length > f "foo" 3 > f "ploeh" 5

This little interactive session uses Haskell, but even if you've never heard about Haskell before, you should still be able to understand what's going on.

A functor is a container of values, for example a collection, a Maybe, a lazy computation, or many other things. If f maps from a to b, then lifting it to the functor F retains the direction. That's what the above figure illustrates. Not only does the functor project a to F a and b to F b, it also maps f to F f, which is F a -> F b.

For lists it might look like this:

> fmap f ["bar", "fnaah", "Gauguin"] [3,5,7]

Here fmap lifts the function String -> Int to [String] -> [Int]. Notice that the types 'go in the same direction' when you lift a function to the functor. The types vary with the function - they co-vary; hence covariance.

While applicative functors and bifunctors are more complex, they are still covariant. Consult, for example, the diagrams in my bifunctor article to get an intuitive sense that this still holds.

Contravariance #

What happens if we change the direction of only one arrow? For example, we could change the direction of the f arrow, so that the function is now a function from b to a: b -> a. The figure would look like this:

This looks almost like the first figure, with one crucial difference: The lower arrow now goes from right to left. Notice that the upper arrow still goes from left to right: F a -> F b. In other words, the functor varies in the contrary direction than the projected function. It's contravariant.

This seems really odd. Why would anyone do that?

As is so often the case with universal abstractions, it's not so much a question of coming up with an odd concept and see what comes of it. It's actually an abstract description of some common programming constructs. In this series of articles, you'll see examples of some contravariant functors:

- The Command Handler contravariant functor

- The Specification contravariant functor

- The Equivalence contravariant functor

- Reader as a contravariant functor

- Functor variance compared to C#'s notion of variance

- Contravariant Dependency Injection

These aren't the only examples, but they should be enough to get the point across. Other examples include equivalence and comparison.

Lifting #

How do you lift a function f to a contravariant functor? For covariant functors (normally just called functors), Haskell has the fmap function, while in C# you'd be writing a family of Select methods. Let's compare. In Haskell, fmap has this type:

fmap :: Functor f => (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

You can read it like this: For any Functor f, fmap lifts a function of the type a -> b to a function of the type f a -> f b. Another way to read this is that given a function a -> b and a container of type f a, you can produce a container of type f b. Due to currying, these two interpretations are both correct.

In C#, you'd be writing a method on Functor<T> that looks like this:

public Functor<TResult> Select<TResult>(Func<T, TResult> selector)

This fits the later interpretation of fmap: Given an instance of Functor<T>, you can call Select with a Func<T, TResult> to produce a Functor<TResult>.

What does the equivalent function look like for contravariant functors? Haskell defines it as:

contramap :: Contravariant f => (b -> a) -> f a -> f b

You can read it like this: For any Contravariant functor f, contramap lifts a function (b -> a) to a function from f a to f b. Or, in the alternative (but equally valid) interpretation that matches C# better, given a function (b -> a) and an f a, you can produce an f b.

In C#, you'd be writing a method on Contravariant<T> that looks like this:

public Contravariant<T1> ContraMap<T1>(Func<T1, T> selector)

The actual generic type (here exemplified by Contravariant<T>) will differ, but the shape of the method will be the same. In order to map from Contravariant<T> to Contravariant<T1>, you need a function that goes the other way: Func<T1, T> goes from T1 to T.

In C#, the function name doesn't have to be ContraMap, since C# doesn't have any built-in understanding of contravariant functors - as opposed to functors, where a method called Select will light up some language features. In this article series I'll stick with ContraMap since I couldn't think of a better name.

Laws #

Like functors, applicative functors, monoids, and other universal abstractions, contravariant functors are characterised by simple laws. The contravariant functor laws are equivalent to the (covariant) functor laws: identity and composition.

In pseudo-Haskell, we can express the identity law as:

contramap id = id

and the composition law as:

contramap (g . f) = contramap f . contramap g

The identity law is equivalent to the first functor law. It states that mapping a contravariant functor with the identity function is equivalent to a no-op. The identity function is a function that returns all input unchanged. (It's called the identity function because it's the identity for the endomorphism monoid.) In F# and Haskell, this is simply a built-in function called id.

In C#, you can write a demonstration of the law as a unit test. Here's the essential part of such a test:

Func<string, string> id = x => x; Contravariant<string> sut = createContravariant(); Assert.Equal(sut, sut.ContraMap(id), comparer);

The ContraMap method does return a new object, so a custom comparer is required to evaluate whether sut is equal to sut.ContraMap(id).

The composition law governs how composition works. Again, notice how lifting reverses the order of functions. In C#, the relevant unit test code might look like this:

Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<int, TimeSpan> g = i => TimeSpan.FromDays(i); Contravariant<TimeSpan> sut = createContravariant(); Assert.Equal( sut.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))), sut.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f), comparer);

This may actually look less surprising in C# than it does in Haskell. Here the lifted composition doesn't look reversed, but that's because C# doesn't have a composition operator for raw functions, so I instead wrote it as a lambda expression: (string s) => g(f(s)). If you contrast this C# example with the equivalent assertion of the (covariant) second functor law, you can see that the function order is flipped: f(g(i)).

Assert.Equal(sut.Select(g).Select(f), sut.Select(i => f(g(i))));

It can be difficult to get your head around the order of contravariant composition without some examples. I'll provide examples in the following articles, but I wanted to leave the definition of the two contravariant functor laws here for reference.

Conclusion #

Contravariant functors are functors that map in the opposite direction of an underlying function. This seems counter-intuitive but describes the actual behaviour of quite normal functions.

This is hardly illuminating without some examples, so without further ado, let's proceed to the first one.

The Reader functor

Normal functions form functors. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. In a previous article you saw, for example, how to implement the Maybe functor in C#. In this article, you'll see another functor example: Reader.

The Reader functor is similar to the Identity functor in the sense that it seems practically useless. If that's the case, then why care about it?

As I wrote about the Identity functor:

"The inutility of Identity doesn't mean that it doesn't exist. The Identity functor exists, whether it's useful or not. You can ignore it, but it still exists. In C# or F# I've never had any use for it (although I've described it before), while it turns out to be occasionally useful in Haskell, where it's built-in. The value of Identity is language-dependent."

The same holds for Reader. It exists. Furthermore, it teaches us something important about ordinary functions.

Reader interface #

Imagine the following interface:

public interface IReader<R, A> { A Run(R environment); }

An IReader object can produce a value of the type A when given a value of the type R. The input is typically called the environment. A Reader reads the environment and produces a value. A possible (although not particularly useful) implementation might be:

public class GuidToStringReader : IReader<Guid, string> { private readonly string format; public GuidToStringReader(string format) { this.format = format; } public string Run(Guid environment) { return environment.ToString(format); } }

This may be a silly example, but it illustrates that a a simple class can implement a constructed version of the interface: IReader<Guid, string>. It also demonstrates that a class can take further arguments via its constructor.

While the IReader interface only takes a single input argument, we know that an argument list is isomorphic to a parameter object or tuple. Thus, IReader is equivalent to every possible function type - up to isomorphism, assuming that unit is also a value.

While the practical utility of the Reader functor may not be immediately apparent, it's hard to argue that it isn't ubiquitous. Every method is (with a bit of hand-waving) a Reader.

Functor #

You can turn the IReader interface into a functor by adding an appropriate Select method:

public static IReader<R, B> Select<A, B, R>(this IReader<R, A> reader, Func<A, B> selector) { return new FuncReader<R, B>(r => selector(reader.Run(r))); } private sealed class FuncReader<R, A> : IReader<R, A> { private readonly Func<R, A> func; public FuncReader(Func<R, A> func) { this.func = func; } public A Run(R environment) { return func(environment); } }

The implementation of Select requires a private class to capture the projected function. FuncReader is, however, an implementation detail.

When you Run a Reader, the output is a value of the type A, and since selector is a function that takes an A value as input, you can use the output of Run as input to selector. Thus, the return type of the lambda expression r => selector(reader.Run(r)) is B. Therefore, Select returns an IReader<R, B>.

Here's an example of using the Select method to project an IReader<Guid, string> to IReader<Guid, int>:

[Fact] public void WrappedFunctorExample() { IReader<Guid, string> r = new GuidToStringReader("N"); IReader<Guid, int> projected = r.Select(s => s.Count(c => c.IsDigit())); var input = new Guid("{CAB5397D-3CF9-40BB-8CBD-B3243B7FDC23}"); Assert.Equal(16, projected.Run(input)); }

The expected result is 16 because the input Guid contains 16 digits (the numbers from 0 to 9). Count them if you don't believe me.

As usual, you can also use query syntax:

[Fact] public void QuerySyntaxFunctorExample() { var projected = from s in new GuidToStringReader("N") select TimeSpan.FromMinutes(s.Length); var input = new Guid("{FE2AB9C6-DDB1-466C-8AAA-C70E02F964B9}"); Assert.Equal(32, projected.Run(input).TotalMinutes); }

The actual computation shown here makes little sense, since the result will always be 32, but it illustrates that arbitrary projections are possible.

Raw functions #

The IReader<R, A> interface isn't really necessary. It was just meant as an introduction to make things a bit easier for object-oriented programmers. You can write a similar Select extension method for any Func<R, A>:

public static Func<R, B> Select<A, B, R>(this Func<R, A> func, Func<A, B> selector) { return r => selector(func(r)); }

Compare this implementation to the one above. It's essentially the same lambda expression, but now Select returns the raw function instead of wrapping it in a class.

In the following, I'll use raw functions instead of the IReader interface.

First functor law #

The Select method obeys the first functor law. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the first functor law for the IReader<R, A> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the first functor law:

[Theory] [InlineData("")] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("antidisestablishmentarianism")] public void FirstFunctorLaw(string input) { T id<T>(T x) => x; Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<string, int> actual = f.Select(id); Assert.Equal(f(input), actual(input)); }

The 'original' Reader f (for function) takes a string as input and returns its length. The id function (which isn't built-in in C#) is implemented as a local function. It returns whichever input it's given.

Since id returns any input without modifying it, it'll also return any number produced by f without modification.

To evaluate whether f is equal to f.Select(id), the assertion calls both functions with the same input. If the functions have equal behaviour, they ought to return the same output.

The above test cases all pass.

Second functor law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that a function (Reader) obeys the second functor law:

[Theory] [InlineData("")] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("antidisestablishmentarianism")] public void SecondFunctorLaw(string input) { Func<string, int> h = s => s.Length; Func<int, bool> g = i => i % 2 == 0; Func<bool, char> f = b => b ? 't' : 'f'; Assert.Equal( h.Select(g).Select(f)(input), h.Select(i => f(g(i)))(input)); }

You can't easily compare two different functions for equality, so, like above, this test defines equality as the functions producing the same result when you invoke them.

Again, while the test doesn't prove anything, it demonstrates that for the five test cases, it doesn't matter if you project the 'original' Reader h in one or two steps.

Haskell #

In Haskell, normal functions a -> b are already Functor instances, which means that you can easily replicate the functions from the SecondFunctorLaw test:

> h = length > g i = i `mod` 2 == 0 > f b = if b then 't' else 'f' > (fmap f $ fmap g $ h) "ploeh" 'f'

Here f, g, and h are equivalent to their above C# namesakes, while the last line composes the functions stepwise and calls the composition with the input string "ploeh". In Haskell you generally read code from right to left, so this composition corresponds to h.Select(g).Select(f).

Conclusion #

Functions give rise to functors, usually known collectively as the Reader functor. Even in Haskell where this fact is ingrained into the fabric of the language, I rarely make use of it. It just is. In C#, it's likely to be even less useful for practical programming purposes.

That a function a -> b forms a functor, however, is an important insight into just what a function actually is. It describes an essential property of functions. In itself this may still seem underwhelming, but mixed with some other properties (that I'll describe in a future article) it can produce some profound insights. So stay tuned.

Next: The IO functor.

Am I stuck in a local maximum?

On long-standing controversies, biases, and failures of communication.

If you can stay out of politics, Twitter can be a great place to engage in robust discussions. I mostly follow and engage with people in the programming community, and every so often find myself involved in a discussion about one of several long-standing controversies. No, not the tabs-versus-spaces debate, but other debates such as functional versus object-oriented programming, dynamic versus static typing, or oral versus written collaboration.

It happened again the past week, but while this article is a reaction, it's not about the specific debacle. Thus, I'm not going to link to the tweets in question.

These discussion usually leave me wondering why people with decades of industry experience seem to have such profound disagreements.

I might be wrong #

Increasingly, I find myself disagreeing with my heroes. This isn't a comfortable position. Could I be wrong?

I've definitely been wrong before. For example, in my article Types + Properties = Software, I wrote about type systems:

"To the far right, we have a hypothetical language with such a strong type system that, indeed, if it compiles, it works."

To the right, in this context, means more statically typed. While the notion is natural, the sentence is uninformed. When I wrote the article, I hadn't yet read Charles Petzold's excellent Annotated Turing. Although I had heard about the halting problem before reading the book, I hadn't internalised it. I wasn't able to draw inferences based on that labelled concept.

After I read the book, I've come to understand that general-purpose static type system can never prove unequivocally that a generic program works. That's what Church, Turing, and Gödel proved.

I've been writing articles on this blog since January 2009. To date, I've published 582 posts. Some are bound to be misinformed, outdated, or just plain wrong. Due to the sheer volume, I make no consistent effort to retroactively monitor and correct my past self. (I'm happy to engage with specific posts. If you feel that an old post is misleading, erroneous, or the like, please leave a comment.)

For good measure, despite my failure to understand the implications of the halting problem, I'm otherwise happy with the article series Types + Properties = Software. You shouldn't consider this particular example a general condemnation of it. It's just an example of a mistake I made. This time, I'm aware of it, but there are bound to be plenty of other examples where I don't even realise it.

Heroes #

I don't have a formal degree in computer science. As so many others of my age, I began my software career by tinkering with computers and (later) programming. The first five years of my professional career, there wasn't much methodology to the way I approached software development. Self-taught often means that you have to learn everything the hard way.

This changed when I first heard about test-driven development (TDD). I credit Martin Fowler with that. Around the same time I also read Design Patterns. Armed with those two techniques, I was able to rescue a failed software project and bring it to successful completion. I even received an (internal) award for it.

While there's more to skilled programming than test-driven development and patterns, it wasn't a bad place to start. Where, before, I had nothing that even resembled a methodology, now I had a set of practices I could use. This gave me an opportunity to experiment and observe. A few years later, I'd already started to notice some recurring beneficial patterns in the code that I wrote, as well as some limits of TDD.

Still, that was a decade where I voraciously read, attended conferences, and tried to learn from my heroes. I hope that they won't mind that I list them here:

Surely, there were others. I remember being a big fan of Don Box, but he seems to have withdrawn from the public long time ago. There were also .NET trailblazers that I admired and tried to emulate. Later, I learned much from the early luminaries of F#. I'm not going to list all the people I admire here, because the list could never be complete, and I don't wish to leave anyone feeling left out. Related to the point I'm trying to make, all these other wonderful people give me less pause.There's a reason I list those particular heroes. I should include a few more of whom I wasn't aware in my formative years, but whom I've since come to highly respect: Brian Marick and Jessica Kerr.

Why do I mention these heroes of mine?

Bias #

Humans aren't as rational as we'd like to think. We all have plenty of cognitive biases. I'm aware of a few of mine, but I expect most of them to be hidden from me. Sometimes, it's easier to spot the bias in others. Perhaps, by spotting the bias in others, it reveals something about oneself?

I increasingly find myself disagreeing with my heroes. One example is the long-standing controversy about static versus dynamic typing.

I hope I'm not misrepresenting anyone, but the heroes I enumerate above seem to favour dynamic typing over static typing - some more strongly than others. This worries me.

These are people who've taught me a lot; whose opinion I deeply respect, and yet I fail to grasp the benefit of dynamic typing. What are the benefits they gain from their preferred languages that I'm blind to? What am I missing?

Whenever I find myself disagreeing with my heroes, I can't help question my own judgment. Am I biased? Yes, obviously, but in which way? What bias prohibits me from seeing the benefits that are so obvious to them?

It's too easy to jump to conclusions - to erect a dichotomy:

- My heroes are right, and I'm wrong

- My heroes are all wrong, and I'm right

I'm hoping that there's a more nuanced position to take - that the above is a false dichotomy.

What's the problem? #

Perhaps we're really talking past each other. Perhaps we're trying to solve different problems, and thereby arrive at different solutions.

I can only guess at the kinds of problems that my heroes think of when they prefer dynamic languages, and I don't want to misrepresent them. What I can do, however, is outline the kind of problem that I typically have in mind.

I've spent much of my career trying to balance sustainability with correctness. I consider correctness as a prerequisite for all code. As Gerald Weinberg implies, if a program doesn't have to work, anything goes. Thus, sustainability is a major focus for me: how do we develop software that can sustain our organisation now and in the future? How do we structure and organise code so that future change is possible?

Whenever I get into debates, that's implicitly the problem on my mind. It'd probably improve communication if I stated this explicitly going into every debate, but sometimes, I get dragged sideways into a debacle... I do, however, speculate that much disagreement may stem from such implicit assumptions. I bring my biases and implicit problem statements into any discussion. I consider it only human if my interlocutors do the same, but their biases and implicit problem understanding may easily be different than mine. What are they, I wonder?

This seems to happen not only in the debate about dynamic versus static types. I get a similar sense when I discuss collaboration. Most of my heroes seem to advocate for high-band face-to-face collaboration, while I favour asynchronous, written communication. Indeed, I admit that my bias is speaking. I self-identify as a contrarian introvert (although, again, we should be careful not turning introversion versus extroversion into binary classification).

Still, even when I try to account for my bias, I get the sense that my opponents and I may actually try to accomplish a common goal, but by addressing two contrasting problems.

I think and hope that, ultimately, we're trying to accomplish the same goal: to deliver and sustain business capability.

I do get the sense that the proponents of more team co-location, more face-to-face collaboration are coming at the problem from a different direction than I am. Perhaps the problem they're trying to solve is micro-management, red tape, overly bureaucratic processes, and a lack of developer autonomy. I can certainly see that if that's the problem, talking to each other is likely to improve the situation. I'd recommend that too, in such a situation.

Perhaps it's a local Danish (or perhaps Northern European) phenomenon, but that's not the kind of problem I normally encounter. Most organisations who ask for my help essentially have no process. Everything is ad hoc, nothing is written down, deployment is a manual process, and there are meetings and interruptions all the time. Since nothing is written down, decisions aren't recorded, so team members and stakeholders keep having the same meetings over and over. Again, little gets done, but for an entirely different reason than too much bureaucracy. I see this more frequently than too much red tape, so I tend to recommend that people start leaving behind some sort of written trail of what they've been doing. Pull request reviews, for example, are great for that, and I see no incongruity between agile and pull requests.

Shaped by scars #

The inimitable Richard Campbell has phrased our biases as the scars we collect during our careers. If you've deleted the production database one too many times, you develop routines and practices to avoid doing that in the future. If you've mostly worked in an organisation that stifled progress by subjecting you to Brazil-levels of bureaucracy, it's understandable if you develop a preference for less formal methods. And if, like me, you've mostly seen dysfunction manifest as a lack of beneficial practices, you develop a taste for written over oral communication.

Does it go further than that? Are we also shaped by our successes, just like we are shaped by our scars?

The first time I had professional success with a methodology was when I discovered TDD. This made me a true believer in TDD. I'm still a big proponent of TDD, but since I learned what algebraic data types can do in terms of modelling, I see no reason to write a run-time test if I instead can get the compiler to enforce a rule.

In a recent discussion, some of my heroes expressed the opinion that they don't need fancy functional-programming concepts and features to write good code. I'm sure that they don't.

My heroes have written code for decades. While I have met bad programmers with decades of experience, most programmers who last that long ultimately become good programmers. I'm not so worried about them.

The people who need my help are typically younger teams. Statistically, there just aren't that many older programmers around.

When I recommend certain practices or programming techniques, those recommendations are aimed at anyone who care to listen. Usually, I find that the audience who engage with me is predominantly programmers with five to ten years of professional experience.

Anecdotal evidence #

This is a difficult discussion to have. I think that another reason that we keep returning to the same controversies is that we mostly rely on anecdotal evidence. As we progress through our careers, we observe what works and what doesn't, but it's likely that confirmation bias makes us remember the results that we already favour, whereas we conveniently forget about the outcomes that don't fit our preferred narrative.

Could we settle these discussions with more science? Alas, that's difficult.

I can't think of anything better, then, than keep having the same discussions over and over. I try hard to overcome my biases to understand the other side, and now and then, I learn something that I find illuminating. It doesn't seem to be a particularly efficient way to address these difficult questions, but I don't know what else to do. What's the alternative to discussion? To not discuss? To not exchange ideas?

That seems worse.

Conclusion #

In this essay, I've tried to come to grips with an increasing cognitive incongruity that I'm experiencing. I find myself disagreeing with my heroes on a regular basis, and that makes me uncomfortable. Could it be that I'm erecting an echo chamber for myself?

The practices that I follow and endorse work well for me, but could I be stuck in a local maximum?

This essay has been difficult to write. I'm not sure that I've managed to convey my doubts and motivations. Should I have named my heroes, only to describe how I disagree with them? Will it be seen as aggressive?

I hope not. I'm writing about my heroes with reverence and gratitude for all that they've taught me. I mean no harm.

At the same time, I'm struggling with reconciling that they rarely seem to agree with me these days. Perhaps they never did.

The Tennis kata revisited

When you need discriminated unions, but all you have are objects.

After I learned that the Visitor design pattern is isomorphic to sum types (AKA discriminated unions), I wanted to try how easy it is to carry out a translation in practice. For that reason, I decided to translate my go-to F# implementation of the Tennis kata to C#, using the Visitor design pattern everywhere I'd use a discriminated union in F#.

The resulting C# code shows that it is, indeed, possible to 'mechanically' translate discriminated unions to the Visitor design pattern. Given that the Visitor pattern requires multiple interfaces and classes to model just a single discriminated union, it's no surprise that the resulting code is much more complex. As a solution to the Tennis kata itself, all this complexity is unwarranted. On the other hand, as an exercise in getting by with the available tools, it's quite illustrative. If all you have is C# (or a similar language), but you really need discriminated unions, the solution is ready at hand. It'll be complex, but not complicated.

The main insight of this exercise is that translating any discriminated union to a Visitor is, indeed, possible. You can best internalise such insights, however, if you actually do the work yourself. Thus, in this article, I'll only show a few highlights from my own exercise. I highly recommend that you try it yourself.

Typical F# solution #

You can see my typical F# solution in great detail in my article series Types + Properties = Software. To be clear, there are many ways to implement the Tennis kata, even in F#, and the one shown in the articles is neither overly clever nor too boring. As implementations go, this one is quite pedestrian.

My emphasis with that kind of solution to the Tennis kata is on readability, correctness, and testability. Going for a functional architecture automatically addresses the testability concern. In F#, I endeavour to use the excellent type system to make illegal states unrepresentable. Discriminated unions are essential ingredients in that kind of design.

In F#, I'd typically model a Tennis game score as a discriminated union like this:

type Score = | Points of PointsData | Forty of FortyData | Deuce | Advantage of Player | Game of Player

That's not the only discriminated union involved in the implementation. Player is also a discriminated union, and both PointsData and FortyData compose a third discriminated union called Point:

type Point = Love | Fifteen | Thirty

Please refer to the older article for full details of the F# 'domain model'.

This was the sort of design I wanted to try to translate to C#, using the Visitor design pattern in place of discriminated unions.

Player #

In F# you must declare all types and functions before you can use them. To newcomers, this often looks like a constraint, but is actually one of F#'s greatest strengths. Since other types transitively use the Player discriminated union, this is the first type you have to define in an F# code file:

type Player = PlayerOne | PlayerTwo

This one is fairly straightforward to translate to C#. You might reach for an enum, but those aren't really type-safe in C#, since they're little more than glorified integers. Using a discriminated union is safer, so define a Visitor:

public interface IPlayerVisitor<T> { T VisitPlayerOne(); T VisitPlayerTwo(); }

A Visitor interface is where you enumerate the cases of the discriminated union - in this example player one and player two. You can idiomatically prefix each method with Visit as I've done here, but that's optional.

Once you've defined the Visitor, you can declare the 'actual' type you're modelling: the player:

public interface IPlayer { T Accept<T>(IPlayerVisitor<T> visitor); }

Those are only the polymorphic types required to model the discriminated union. You also need to add concrete classes for each of the cases. Here's PlayerOne:

public struct PlayerOne : IPlayer { public T Accept<T>(IPlayerVisitor<T> visitor) { return visitor.VisitPlayerOne(); } }

This is an example of the Visitor pattern's central double dispatch mechanism. Clients of the IPlayer interface will dispatch execution to the Accept method, which again dispatches execution to the visitor.

I decided to make PlayerOne a struct because it holds no data. Perhaps I also ought to have sealed it, or, as Design Patterns likes to suggest, make it a Singleton.

Hardly surprising, PlayerTwo looks almost identical to PlayerOne.

Apart from a single-case discriminated union (which is degenerate), a discriminated union doesn't get any simpler than Player. It has only two cases and carries no data. Even so, it takes four types to translate it to a Visitor: two interfaces and two concrete classes. This highlights how the Visitor pattern adds significant complexity.

And it only gets worse with more complex discriminated unions.

Score #

I'm going to leave the translation of Point as an exercise. It's similar to the translation of Player, but instead of two cases, it enumerates three cases. Instead, consider how to enumerate the cases of Score. First, add a Visitor:

public interface IScoreVisitor<T> { T VisitPoints(IPoint playerOnePoint, IPoint playerTwoPoint); T VisitForty(IPlayer player, IPoint otherPlayerPoint); T VisitDeuce(); T VisitAdvantage(IPlayer advantagedPlayer); T VisitGame(IPlayer playerWhoWonGame); }

Notice that these methods take arguments, apart from VisitDeuce. I could have made that member a read-only property instead, but for consistency's sake, I kept it as a method.

All the other methods take arguments that are, in their own right, Visitors.

In addition to the Visitor interface, you also need an interface to model the score itself:

public interface IScore { T Accept<T>(IScoreVisitor<T> visitor); }

This one defines, as usual, just a single Accept method.

Since IScoreVisitor enumerates five distinct cases, you must also add five concrete implementations of IScore. Here's Forty:

public struct Forty : IScore { private readonly IPlayer player; private readonly IPoint otherPlayerPoint; public Forty(IPlayer player, IPoint otherPlayerPoint) { this.player = player; this.otherPlayerPoint = otherPlayerPoint; } public T Accept<T>(IScoreVisitor<T> visitor) { return visitor.VisitForty(player, otherPlayerPoint); } }

I'm leaving other concrete classes as an exercise to the reader. All of them are similar, though, in that they all implement IScore and unconditionally dispatch to 'their' method on IScoreVisitor - Forty calls VisitForty, Points calls VisitPoints, and so on. Each concrete implementation has a distinct constructor, though, since what they need to dispatch to the Visitor differs.

Deuce, being degenerate, doesn't have to explicitly define a constructor:

public struct Deuce : IScore { public T Accept<T>(IScoreVisitor<T> visitor) { return visitor.VisitDeuce(); } }

The C# compiler automatically adds a parameterless constructor when none is defined. An alternative implementation would, again, be to make Deuce a Singleton.

In all, it takes seven types (two interfaces and five concrete classes) to model Score - a type that requires only a few lines of code in F# (six lines in my code, but you could format it more densely if you want to compromise readability).

Keeping score #

In order to calculate the score of a game, I also translated the score function. I put that in an extension method so as to not 'pollute' the IScore interface:

public static IScore BallTo(this IScore score, IPlayer playerWhoWinsBall) { return score.Accept(new ScoreVisitor(playerWhoWinsBall)); }

Given an IScore value, there's little you can do with it, apart from calling its Accept method. In order to do that, you'll need an IScoreVisitor, which I defined as a private nested class:

private class ScoreVisitor : IScoreVisitor<IScore> { private readonly IPlayer playerWhoWinsBall; public ScoreVisitor(IPlayer playerWhoWinsBall) { this.playerWhoWinsBall = playerWhoWinsBall; } // Implementation goes here...

Some of the methods are trivial to implement, like VisitDeuce:

public IScore VisitDeuce() { return new Advantage(playerWhoWinsBall); }

Most others are more complicated. Keep in mind that the method arguments (IPlayer, IPoint) are Visitors in their own right, so in order to do anything useful with them, you'll have to call their Accept methods with a corresponding, specialised Visitor.

Pattern matching #

I quickly realised that this would become too tedious, even for an exercise, so I leveraged my knowledge that the Visitor pattern is isomorphic to a Church encoding. Instead of defining umpteen specialised Visitors, I just defined a generic Match method for each Visitor-based object. I put those in extension methods as well. Here's the Match method for IPlayer:

public static T Match<T>(this IPlayer player, T playerOne, T playerTwo) { return player.Accept(new MatchVisitor<T>(playerOne, playerTwo)); }

The implementation is based on a private nested MatchVisitor:

private class MatchVisitor<T> : IPlayerVisitor<T> { private readonly T playerOneValue; private readonly T playerTwoValue; public MatchVisitor(T playerOneValue, T playerTwoValue) { this.playerOneValue = playerOneValue; this.playerTwoValue = playerTwoValue; } public T VisitPlayerOne() { return playerOneValue; } public T VisitPlayerTwo() { return playerTwoValue; } }

This enables pattern matching, upon which you can implement other reusable methods, such as Other:

public static IPlayer Other(this IPlayer player) { return player.Match<IPlayer>( playerOne: new PlayerTwo(), playerTwo: new PlayerOne()); }

It's also useful to be able to compare two players and return two alternative values depending on the result:

public static T Equals<T>( this IPlayer p1, IPlayer p2, T same, T different) { return p1.Match( playerOne: p2.Match( playerOne: same, playerTwo: different), playerTwo: p2.Match( playerOne: different, playerTwo: same)); }

You can add similar Match and Equals extension methods for IPoint, which enables you to implement all the methods of the ScoreVisitor class. Here's VisitForty as an example:

public IScore VisitForty(IPlayer player, IPoint otherPlayerPoint) { return playerWhoWinsBall.Equals(player, same: new Game(player), different: otherPlayerPoint.Match<IScore>( love: new Forty(player, new Fifteen()), fifteen: new Forty(player, new Thirty()), thirty: new Deuce())); }

If playerWhoWinsBall.Equals(player the implementation matches on same, and returns new Game(player). Otherwise, it matches on different, in which case it then has to Match on otherPlayerPoint to figure out what to return.

Again, I'll leave the remaining code as an exercise to the reader.

Tests #

While all this code is written in C#, it's all pure functions. Thus, it's intrinsically testable. Knowing that, I could have added tests after writing the 'production code', but that's so boring, so I still developed this code base using test-driven development. Here's an example of a test:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(Player))] public void TransitionFromDeuce(IPlayer player) { var sut = new Deuce(); var actual = sut.BallTo(player); var expected = new Advantage(player); Assert.Equal(expected, actual); }

I wrote all tests as properties for all. The above test uses xUnit.net 2.4.0. The Player data source is a private MemberData defined as a read-only property:

public static IEnumerable<object[]> Player { get { yield return new object[] { new PlayerOne() }; yield return new object[] { new PlayerTwo() }; } }

Other tests are defined in a likewise manner.

Conclusion #

Once you've tried to solve problems with algebraic data types it can be frustrating to return to languages that don't have sum types (discriminated unions). There's no need to despair, though. Sum types are isomorphic to the Visitor design pattern, so it is possible to solve problems in the same way.

The resulting code can easily seem complex because a simple discriminated union translates to multiple C# files. Another option is to use Church encoding, but many developers who consider themselves object-oriented often balk at such constructs. When it comes to policy, the Visitor design pattern offers the advantage that it's described in Design Patterns. While it may be a bit of an underhanded tactic, it effectively deals with some teams' resistance to ideas originating in functional programming.

The exercise outlined in this article demonstrates that translating from algebraic data types to patterns-based object-oriented code is not only possible, but (once you get the hang of it) unthinking and routine. It's entirely automatable, so you could even imagine defining a DSL for defining sum types and transpiling them to C#.

But really, you don't have to, because such a DSL already exists.

Comments

The most annoying thing about the visitor pattern is that you can't get around declaring

interface IMyLovelyADT { R Accept<R>(IMyLovelyADTVisitor<R> visitor); }

and a separate class implementing this interface for each data variant. One may think that this interface is isomorphic to

Func<IMyLovelyADTVisitor<R>, R> but it actually is not, look:

// type Bool = True | False

interface IBoolVisitor<R>

{

R True();

R False();

}

static class BoolUtils

{

public static Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R> True<R>() => sym => sym.True();

public static Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R> False<R>() => sym => sym.False();

private class BoolMatcher<R> : IBoolVisitor<R>

{

Func<R> OnTrue { get; }

Func<R> OnFalse { get; }

public BoolMatcher(Func<R> onTrue, Func<R> onFalse)

{

OnTrue = onTrue;

OnFalse = onFalse;

}

public R True() => OnTrue();

public R False() => OnFalse();

}

public static R Match<R>(this Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R> value, Func<R> onTrue, Func<R> onFalse) => value(new BoolMatcher<R>(onTrue, onFalse));

}

Yes, all this typechecks and compiles, and you can even write ShowBool and BoolToInt methods, but!

You can't combine them:

static class FunctionsAttempt1

{

public static string ShowBool(Func<IBoolVisitor<string>, string> value)

{

return value.Match(() => "True", () => "False");

}

public static int BoolToInt(Func<IBoolVisitor<int>, int> value)

{

return value.Match(() => 1, () => 0);

}

public static string CombineBoolFunctions<R>(Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R> value)

{

return ShowBool(value) + ": " + BoolToInt(value).ToString();

}

}

The first two methods are fine, but CombineBoolFunctions doesn't compile, because you can't pass

Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R> to a method that expects

Func<IBoolVisitor<string>, string>.

What if you try to make ShowBool and BoolToInt accept Func<IBoolVisitor<R>, R>?

static class FunctionsAttempt2

{

public static string ShowBool(Func<>, R> value)

{

return value.Match(() => "True", () => "False");

}

public static int BoolToInt(Func<>, R> value)

{

return value.Match(() => 1, () => 0);

}

public static string CombineBoolFunctions(Func<>, R> value)

{

return ShowBool(value) + ": " + BoolToInt(value).ToString();

}

}

That also doesn't work, for pretty much the same reason: CombineBoolFunctions compiles now, but not

ShowBool or BoolToInt. That's why you need a non-generic wrapper interface IMyLovelyADT:

it essentially does the same job as Haskell's forall, since generic types are not quite proper types in C#'s type system.

Interestingly enough, upcoming Go 2's generics will not support this scenario: a method inside an interface will be able to use

only the generic parameters that the interface itself declares.

Joker_vD, thank you for writing; you explained that well.

I've recently been using C# 9's record feature to implement ADTs. For example:

public abstract record Player

{

private Player() {}

public sealed record One : Player;

public sealed record Two : Player;

}

public abstract record Point

{

private Point() {}

public sealed record Love: Point;

public sealed record Fifteen: Point;

public sealed record Thirty: Point;

}

public abstract record Score

{

private Score() {}

public sealed record Points(Point PlayerOnePoints, Point PlayerTwoPoints);

public sealed record Forty(Player Player, Point OtherPlayersPoint);

public sealed record Deuce;

public sealed record Advantage(Player Player);

public sealed record Game(Player Player);

}

It's not as good as F# ADTs, but it's more concise than Visitors, works with switch pattern matching,

has structural equality semantics, and I haven't found the downside yet.

Tyrie, thank you for writing. I haven't tried that yet, but I agree that if this works, it's simpler.

Does switch pattern matching check exhaustiveness? What I means is: With sum types/discriminated unions, as well as with the Visitor pattern, the compiler can tell you if you haven't covered all cases. Does the C# compiler also do that with switch pattern matching?

And do you need to include a default label?

Looks like you found the flaw. The C# compiler tries, and it will block invalid cases, but it always wants a default case (either _ or both "null" and "not null")

when switching on one of these. It can't suggest the actually missing cases.

It's also only a warning by default at compile time.

Referential transparency fits in your head

Why functional programming matters.

This article is mostly excerpts from my book Code That Fits in Your Head. The overall message is too important to exclusively hide away in a book, though, which is the reason I also publish it here.

The illustrations are preliminary. While writing the manuscript, I experimented with hand-drawn figures, but Addison-Wesley prefers 'professional' illustrations. In the published book, the illustrations shown here will be replaced by cleaner, more readable, but also more boring figures.

Nested composition #

Ultimately, software interacts with the real world. It paints pixels on the screen, saves data in databases, sends emails, posts on social media, controls industrial robots, etcetera. All of these are what we in the context of Command Query Separation call side effects.

Since side effects are software's raison d'être, it seems only natural to model composition around them. This is how most people tend to approach object-oriented design. You model actions.

Object-oriented composition tends to focus on composing side effects together. The Composite design pattern may be the paragon of this style of composition, but most of the patterns in Design Patterns rely heavily on composition of side effects.

As illustrated in [the following figure] this style of composition relies on nesting objects in other objects, or side effects in other side effects. Since your goal should be code that fits in your head, this is a problem.

[Figure caption:] The typical composition of objects (or, rather, methods on objects) is nesting. The more you compose, the less the composition fits in your brain. In this figure, each star indicates a side effect that you care about. Object A encapsulates one side effect, and object B two. Object C composes A and B, but also adds a fourth side effect. That's already four side effects that you need to keep in mind when trying to understand the code. This easily gets out of hand: object E composes a total of eight side effects, and F nine. Those don't fit well in your brain.

I should add here that one of the book's central tenets is that the human short-term memory can only hold a limited amount of information. Code that fits in your head is code that respects that limitation. This is a topic I've already addressed in my Humane Code video.

In the book, I use the number seven as a symbol of the this cognitive limit. Nothing I argue, however, relies on this exact number. The point is only that short-term memory is quite limited. Seven is only a shorthand for that.

The book proceeds to provide a code example that illustrates how fast nested composition accumulates complexity that exceeds the capacity of your short-term memory. You can see the code example in the book, or in the article Good names are skin-deep, which makes a slightly different criticism than the one argued in the book.

The section on nested composition goes on:

"Abstraction is the elimination of the irrelevant and the amplification of the essential"

By hiding a side effect in a Query, I've eliminated something essential. In other words, more is going on in [the book's code listing] than meets the eye. The cyclomatic complexity may be as low as 4, but there's a hidden fifth action that you ought to be aware of.

Granted, five chunks still fit in your brain, but that single hidden interaction is an extra 14% towards the budget of seven. It doesn't take many hidden side effects before the code no longer fits in your head

Sequential composition #

While nested composition is problematic, it isn't the only way to compose things. You can also compose behaviour by chaining it together, as illustrated in [the following figure].

[Figure caption:] Sequential composition of two functions. The output from

Wherebecomes the input toAllocate.In the terminology of Command Query Separation, Commands cause trouble. Queries, on the other hand, tend to cause little trouble. They return data which you can use as input for other Queries.

Again, the book proceeds to show code examples. You can, of course, see the code in the book, but the methods discussed are the WillAccept function shown here, the Overlaps function shown here, as well as a few other functions that I don't think that I've shown on the blog.

The entire restaurant example code base is written with that principle in mind. Consider the

WillAcceptmethod [...]. After all the Guard Clauses it first creates a new instance of theSeatingclass. You can think of a constructor as a Query under the condition that it has no side effects.The next line of code filters the

existingReservationsusing theOverlapsmethod [...] as a predicate. The built-inWheremethod is a Query.Finally, the